Quick Facts

| Field | Detail |

|---|---|

| Full name | Theodosia Patricia Thomas |

| Year of birth | 1938 |

| Birthplace | Nashville, Tennessee |

| Parents | Vivien Theodore Thomas (1910–1985), Clara Beatrice Flanders Thomas |

| Sibling | Olga Fay Thomas (b. 1934 — d. 2020) |

| Education | Attended Morgan State College (now Morgan State University) — mid-1950s–1960s |

| Residence (family move) | Baltimore, Maryland (family relocated 1941) |

| Public profile | Low; minimal social media mentions; tied largely to her father’s legacy |

| Status (as of 2025) | Likely living — no public obituary located |

Early Life and Family Roots

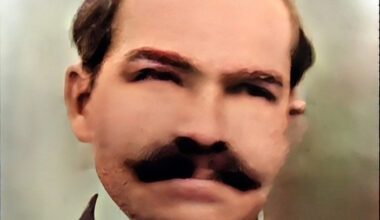

Born in 1938 in Nashville, Theodosia Patricia Thomas arrived into a household marked by quiet ambition and constrained possibility. Her father, Vivien Theodore Thomas, born in 1910, carried the kind of ingenuity that reads like a secret engine in the family’s story — self-taught, tenacious, and repeatedly thwarted by the era’s racial barriers. The family moved when she was about 3 years old: in 1941 they relocated to Baltimore so Vivien could work alongside Dr. Alfred Blalock at Johns Hopkins. That move etched the family’s life into the map of American medical progress.

Growing up amid segregation, Theodosia’s childhood was shaped less by headlines and more by household rules: education first, dignity always, and endurance as a daily practice. The household’s steady light was Clara Beatrice Flanders Thomas, the mother who guided two daughters through a world that offered limited doors. Olga, the elder sister (born 1934), and Theodosia were raised to see learning as a ladder—one rung at a time.

Education and Values

Theodosia’s time at Morgan State College in the mid-1950s to 1960s placed her inside a historic Black institution during a period of national upheaval. Numbers matter here: she matriculated at a moment when fewer than 5% of Americans completed college; for Black women of her generation, the figure was far lower. That she pursued higher education is a measurable testament to family priorities and personal resolve.

Education in the Thomas household was more than credential-gaining. It was a mechanism of resistance. Where barriers existed, study was the quiet tool for climbing over them. Where recognition was withheld, accomplishment at an HBCU became its own kind of ledger entry: proof that potential had been cultivated, even if the wider world refused to tally it.

A Life Beside a Medical Giant

Vivien Thomas’s professional achievements are part of Theodosia’s life story by proximity and gravity. The Blalock-Thomas-Taussig shunt, developed in the early 1940s and widely credited with transforming treatment for cyanotic congenital heart defects, anchored the household narrative. Vivien’s work — emergent from ingenuity rather than formal entitlement — cast long shadows and bright halos. He received public institutional recognition late in life: an honorary doctorate in 1976, and he died in 1985 at age 75.

Theodosia lived in the radius of that work: present at family gatherings, witness to the complicated ledger of acclaim and omission, and beneficiary of lessons passed down about humility and stamina. Her presence in family narratives functions as ballast—steady, unflashy, impossible to separate from the motion of the rest of the family.

Family Table: Relatives and Roles

| Name | Relationship | Years / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Vivien Theodore Thomas | Father | 1910–1985; key figure in cardiac surgical history |

| Clara Beatrice Flanders Thomas | Mother | Married 1933; family anchor |

| Olga Fay Thomas (Norris) | Older sister | 1934–2020; attended Morgan State; active in family legacy projects |

| William Maceo Thomas | Paternal grandfather | Limited public detail; family roots in Louisiana |

| Mary Eaton Thomas | Paternal grandmother | Limited public detail |

| Harold Thomas | Paternal uncle | Sparse public records |

| Three unnamed granddaughters | Next generation | Listed among Vivien’s survivors; identities private |

Public Presence, Privacy, and the Quiet Archive

Despite a family linked to a medical landmark, Theodosia’s own record is deliberately sparse. There are no publicized career milestones attached to her name, no documented awards, and no established public persona beyond familial connection. This scarcity is itself a kind of statement: a life chosen out of the limelight.

Privacy sometimes functions like a moat. Where public archives end, family memory continues—oral histories, small acts of stewardship, a willingness to keep certain things within the household. For historians and biographers, that moat is frustrating. For family members, it may be deliberate and protective.

Timeline: Selected Dates and Ages

| Year | Event | Age |

|---|---|---|

| 1910 | Vivien Thomas born | — |

| 1933 | Vivien and Clara marry | — |

| 1934 | Olga Fay Thomas born | — |

| 1938 | Theodosia Patricia Thomas born (Nashville) | 0 |

| 1941 | Family moves to Baltimore | Theodosia: 3 |

| 1944 | Blalock-Thomas-Taussig shunt developed | Theodosia: 6 |

| Mid-1950s–1960s | Theodosia attends Morgan State College | Approx. 17–27 |

| 1976 | Vivien receives honorary doctorate | Theodosia: ~38 |

| 1985 | Vivien dies (pancreatic cancer) | Theodosia: ~47 |

| 2020 | Olga (sister) dies | Theodosia: ~82 |

| 2025 | No public obituary for Theodosia; social mentions tied to family legacy | Theodosia: ~87 |

The Shape of a Private Life

Numbers and dates outline a skeleton. Theodosia’s life, as visible from surviving public traces, fills in with quieter details: attendance at an HBCU during a pivotal era; upbringing in a home where a parent’s genius was both asset and injustice; adulthood lived largely out of public view. She is the kind of person who exists at the confluence of great public deeds and private restraint.

Her story is not a single headline. It is a ledger with few entries but deep margins—annotations of loyalty, education, and discretion. In the photograph of the family, she is not the flash of the camera but the calm hand steadying the frame.